In the wake of the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank International, a section of the patent statute once the focus of only occasional litigation is emerging as a “go to” weapon for invalidating patents directed to computer-implemented inventions. Of the 25 federal court decisions in which 35 U.S.C. § 101 (Section 101) has been invoked since Alice was handed down, 19 have resulted in declarations of invalidity. This article highlights some trends in the case law. It also examines more closely one recent Federal Circuit decision in which patent claims did not survive a preliminary challenge under Section 101, as well as the six decisions in which the claims did survive.

By way of background, at issue in Alice was whether claims to use of a computer acting in the role of a third-party intermediary to a financial transaction were eligible for patenting under Section 101. Reiterating a two-part test it had previously laid down in determining the patent-eligibility of a method of medical treatment, the Supreme Court said that proper analysis required determining whether the claims at issue were directed to concepts ineligible for patenting (i.e., laws of nature, natural phenomenon, or abstract ideas) and, if so, whether that concept was transformed into something which amounts to “significantly more” than the concept itself. Applying that test to the claims at hand, the Court held that they covered no more than a generic computer implementation of the abstract idea of risk intermediation and, as such, were not patent-eligible.

Lower court decisions on computer-implemented inventions since Alice have applied that same test to challenges under Section 101, and several points from these cases are worth noting:

- The lower courts have continued to apply pre-Alice tests of patent eligibility—including the machine-or-transformation and “mental process” tests—to supplement analyses under the two-part framework reiterated in Alice.

- In determining whether claims cover “abstract ideas,” the lower courts have looked to prior rulings on claims analogous to those at hand. The Supreme Court had done likewise in Alice, equating the intermediated settlement claims before it with risk hedging claims held patent-ineligible by the Court four years earlier in Bilski v. Kappos.

- The lower courts are giving weight to the safe harbors enunciated in Alice for claims that “improve the functioning of the computer itself” or that “effect an improvement in any other technology or technical field.”

- Section 101 challenges have proven dispositive in summary judgment motions, as well as in motions to dismiss, though as to the latter the courts have shown reluctance to decide patent-eligibility at such an early stage in litigation.

A brief overview follows of six post-Alice district court cases in which the claims survived a Section 101 challenge. Also discussed is a recent Federal Circuit decision in which the claims did not survive such a challenge.

Ultramercial, LLC v. Hulu, Inc., 2010-1544 (Fed. Cir. Nov. 14, 2014)

The Ultramercial opinion, handed down last week, is the Federal Circuit’s third decision on U.S. Patent No. 7,346,545 (“the ‘545 patent”). In its prior, pre-Alice decisions, the Federal Circuit had reversed lower court holdings of patent ineligibility. Now, after Alice, the appeals court has reached the opposite conclusion, finding that the claimed subject matter is patent-ineligible.

The ‘545 patent is directed to methods for distributing video and other content over the Internet to viewers in exchange for their watching advertisements. Representative claim 1 recites:

1. A method for distribution of products over the Internet via a facilitator, said method comprising the steps of:

a first step of receiving, from a content provider, media products that are covered by intellectual-property rights protection and are available for purchase, wherein each said media product being comprised of at least one of text data, music data, and video data;

a second step of selecting a sponsor message to be associated with the media product, said sponsor message being selected from a plurality of sponsor messages, said second step including accessing an activity log to verify that the total number of times which the sponsor message has been previously presented is less than the number of transaction cycles contracted by the sponsor of the sponsor message;

a third step of providing the media product for sale at an Internet website;

a fourth step of restricting general public access to said media product;

a fifth step of offering to a consumer access to the media product without charge to the consumer on the precondition that the consumer views the sponsor message;

a sixth step of receiving from the consumer a request to view the sponsor message, wherein the consumer submits said request in response to being offered access to the media product;

a seventh step of, in response to receiving the request from the consumer, facilitating the display of a sponsor message to the consumer;

an eighth step of, if the sponsor message is not an interactive message, allowing said consumer access to said media product after said step of facilitating the display of said sponsor message;

a ninth step of, if the sponsor message is an interactive message, presenting at least one query to the consumer and allowing said consumer access to said media product after receiving a response to said at least one query;

a tenth step of recording the transaction event to the activity log, said tenth step including updating the total number of times the sponsor message has been presented; and

an eleventh step of receiving payment from the sponsor of the sponsor message displayed.

The court summarized the claims as directed to a process of receiving copyrighted media, selecting an ad, offering the media in exchange for watching the selected ad, displaying the ad, allowing the consumer access to the media, and receiving payment from the sponsor of the ad. It acknowledged that the summary ignored “certain additional limitations, such as consulting an activity log, [which] add a degree of particularity” to the invention. However, the court dismissed the contention that the claims were directed to a specific method previously unknown in the art and, hence, could not be characterized as the sort of abstract idea within the purview of Alice. Concluding its analysis under the first step of the Alice framework, the court adopted the district court characterization, stating that the abstract idea “at the heart of the ’545 patent was ‘that one can use [an] advertisement as an exchange or currency.’”

Turning to the second step of the Alice framework, the appeals court concluded that the claims were devoid of limitations sufficient to impart patent eligibility. It characterized the additional limitations “such as updating an activity log, requiring a request from the consumer to view the ad, restrictions on public access, and use of the Internet” as routine. And even if some of the steps recited in the claims were not previously known in the art, the court commented, that alone was not enough for patent eligibility.

The court in Ultramercial applied the machine-or-transformation test to supplement its analysis under the second step of Alice. Notwithstanding that the claims of the ’545 patent were tied to the Internet, the court said that this was not sufficient to save the patent since the Internet “is a ubiquitous information-transmitting medium, not a novel machine.” The additional recitation of a computer went no further toward saving the claims from patent ineligibility, the court went on, noting that “any transformation from the use of computers or the transfer of content between computers is merely what computers do and does not change the analysis.”

Practitioners may find the tenor, if not the outcome, of Ultramercial unsettling. The language of the decision raises the specter of a broad-ranging attack on software patents. The majority opinion attempts to quell those concerns, observing at “some level, ‘all inventions… embody, use, reflect, rest upon, or apply laws of nature, natural phenomena, or abstract ideas.’… We acknowledge this reality, and we do not purport to state that all claims in all software-based patents will necessarily be directed to an abstract idea.” Perhaps more telling of what the bar can expect from the Federal Circuit following Ultramercial is the statement by Judge Mayer in the opening paragraph of his concurring opinion: “Because the purported inventive concept in Ultramercial’s asserted claims is an entrepreneurial rather than a technological one, they fall outside section 101.”

Ameranth, Inc. v. Genesis Gaming Solutions, Inc., 8:11-cv-00189 (C.D. Cal. Nov. 12, 2014)

In Ameranth, the district court denied the defendant’s motion for summary judgment of invalidity under Section 101. The asserted claims were directed to methods for monitoring a casino poker game. A representative claim of the patent follows:

1. A computerized method for monitoring a physical casino poker game comprising:

a. receiving a poker player check-in input containing player identification information and player poker game type preference;

b. identifying a particular player in a player database from the player check-in input;

c. determining the seating availability for said particular player's poker game type preference from a table availability database including game types in real time;

d. adding said particular player to a waitlist for said poker game type preference if no matching table for said game type is currently available;

e. displaying indicia identifying said particular player on a public waitlist display, said public display including the display of information comprising at least two different poker game types and waiting players for each game type and wherein said public display is suitable for viewing by a multiplicity of players or prospective players throughout the poker room;

f. selecting a table for said particular waiting player matching said waiting player's selected game type when it is available and then assigning said player to that available table;

g. receiving check-out input regarding said particular player containing player identification information;

h. identifying the particular player from the player check-out input information;

i. removing the player from the game and from the table;

j. updating the table availability to reflect that a seat for the particular poker game type at said table is currently available;

k. ascertaining the total elapsed time between receiving the check-in input and the check-out input of the player;

l. transmitting the total elapsed time to a compensation system; and

m. calculating an amount of compensation for the particular player based on the total elapsed time and storing the calculated compensation in at least one of a system database or the player database.

The defendant alleged that the claims were directed to the abstract concept of a customer loyalty program, relying primarily on the recited step of calculating an amount of compensation for the player. The court disagreed, noting that steps c, d, e, and f of claim 1 were not required for a customer loyalty program and that the defendant had not explained why those steps should be ignored when identifying the abstract idea. Further, the court found that the defendant had not shown why these steps did not provide the “significantly more” required under the second prong of the Alice test. As noted by the court, “one could implement many different player reward systems that do not infringe the claims.” It thus concluded that the claims did not raise the specter of preemption and denied the defendant’s motion.

In Caltech, the district court denied the defendant’s motion for summary judgment of invalidity under Section 101. The asserted claims were directed to methods of encoding and decoding data in a digital communication system using an irregular repeat and accumulate (IRA) code. IRA codes are said to “balance competing goals: data accuracy and efficiency.” A representative claim is as follows:

1. A method comprising:

receiving a collection of message bits having a first sequence in a source data stream;

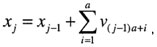

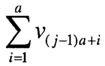

generating a sequence of parity bits, wherein each parity bit "xj" in the sequence is in accordance with the formula

where "xj-1" is the value of a parity bit "j-1," and

is the value of a sum of "a" randomly chosen irregular repeats of the message bits; and

making the sequence of parity bits available for transmission in a transmission data stream.

Caltech provides a comprehensive analysis of Supreme Court and Federal Circuit precedent on Section 101. Looking to the then-existing1 post-Alice Federal Circuit decisions concerning Section 101, for example, the court in Caltech criticized one for “providing false guidance to district courts” and potentially “eviscerating software patents,” and the two others as offering “no guidance at all” by virtue of involving “obvious examples of ineligibility.” The Caltech decision also dismisses a prior case decided in the same district, in which a point-of-novelty approach was applied in connection with the Section 101 analysis.

Significantly, the court in Caltech concluded that software is not ineligible per se, noting that Alice “left open the possibility that claims which improve the functioning of the computer itself or any other technology are patentable” and that Congress had clearly contemplated that software is patent-eligible when they included “computer program products” in various sections of the America Invents Act (AIA).

Turning to the claims at issue, the court in Caltech noted that in carrying out the first step of the Alice framework, the arbiter “must identify the purpose of the claim—in other words, what the claimed invention is trying to achieve—and ask whether that purpose is abstract,” keeping in mind that “prior art plays no role in this step” and that “age-old ideas are likely abstract, in addition to basic tools of research and development, like natural laws and fundamental mathematical relationships.” Applying these principles, the court concluded that the claims at issue were indeed directed to the abstract idea of encoding and decoding data for the purpose of achieving error correction.

Under the second step of the Alice framework, the court found that the claims provided a sufficient inventive concept to render them patent-eligible, noting that “when claims provide a specific computing solution for a computing problem, these claims should generally be patentable, even if their novel elements are mathematical algorithms.” In particular, the court found that the irregular repetition of bits and use of linear transform operations added meaningful limitations to the abstract idea. These limitations were narrowly defined, tied to a specific error correction process, not necessary or obvious tools for achieving error correction, and ensured that the claims did not preempt the field of error correction.

While the “mental steps” or “pencil-and-paper” doctrines might have led to the opposite conclusion, the Caltech court found them to be unhelpful in evaluating computer-implemented inventions under Section 101. The court reasoned that, while a human could arguably spend months or years doing on paper the calculations that are claimed as software, that effort would never produce the same result as the software. Concluding that the asserted claims “improve[d] a computer’s functionality by applying concepts unique to computing to solve a problem unique to computing” the court in Caltech denied the defendant’s motion.

In Card Verification Solutions, the district court denied the defendant’s 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss on the ground of invalidity under Section 101. The asserted claims were directed to methods of passing confidential information such as a credit card number over an unsecured network by dividing the information into multiple parts and attaching randomly-generated tags to each part. A representative claim is as follows:

1. A method for giving verification information for a transaction between an initiating party and a verification-seeking party, the verification information being given by a third, verifying party, based on confidential information in the possession of the initiating party, the method comprising:

on behalf of the initiating party, generating first and second tokens each of which represents some but not all of the confidential information,

sending the first token electronically via a nonsecure communication network from the initiating party to the verification-seeking party,

sending the second token electronically via a nonsecure communication network from the initiating party to the verifying party,

sending the first token electronically via a nonsecure communication network from the verification-seeking party to the verifying party,

verifying the confidential information at the verifying party based on the first and second tokens, and sending the verification information electronically via a nonsecure communication network from the verifying party to the verification-seeking party.

Applying the first prong of the Alice framework, the court held that the claims were directed to the abstract idea of “verifying a transaction.” For the second prong of the Alice framework, the court found that the claims plausibly recited a patent-eligible application of that abstract idea. In particular, the court noted that “the claims may be sufficiently limited by the plausible transformation that occurs when the randomly-generated tag is added to the piece of confidential information,” and that “[the claimed method] utilizes a system for modifying data that may have a concrete effect in the field of electronic communications.” The court also found that the claims may satisfy both the mental process test and machine-or-transformation test. Accordingly, the defendant’s motion to dismiss on the ground of invalidity under Section 101was denied.

Helios Software, LLC v. SpectorSoft Corp., 2014 WL 4796111 (D. Del. Sept. 18, 2014)

In Helios, the court granted the plaintiff’s motion for summary judgment as to Section 101 eligibility of the asserted claims. The claims were directed to methods of monitoring data associated with an Internet session and methods of controlling computer network access. A representative claim is as follows:

1. A method of remotely monitoring an exchange of data between a local computer and a remote computer during an Internet session over the Internet, the method comprising the steps of:

(a) storing at a local computer an Internet server address and port number of a monitor computer;

(b) initiating a first Internet session between the local computer and a remote computer via the Internet;

(c) storing at the local computer data associated with the first Internet session;

(d) retrieving the Internet server address and port number stored at the local computer;

(e) initiating concurrent with the first Internet session a second Internet session between the local computer and the monitor computer at the retrieved Internet server address and port number;

(f) transmitting from the monitor computer to the local computer at least one of another Internet server address and another port number;

(g) terminating the second Internet session;

(h) initiating concurrent with the first Internet session a third Internet session between the local computer and the monitor computer using the other Internet server address and/or the other port number; and

(i) transferring from the local computer to the monitor computer via the third Internet session the stored data associated with the first Internet session.

The court first found that the defendant had failed to provide any support for the position that “remotely monitoring data associated with an Internet session” or “controlling network access” were fundamental principles that could constitute abstract ideas under the first prong of the Alice framework. The court went on to state that “even if the asserted claims were drawn to abstract ideas, they would remain patentable because they satisfy the machine-or-transformation test.” In particular, the court noted that (1) the claims recite “meaningful limitations by claiming exchanging data over different internet sessions to capture the content of an ongoing Internet communication session”; (2) by claiming real-time data capture, transmission, and reception, the computer plays a significant part in permitting the claimed methods to be performed; and (3) the ability to provide access configurations and communication protocols that control computer network access and monitor activity are “meaningful limitations [that] limit the scope of the patented invention and sufficiently tie the claimed method to a machine.” The claims were thus held to be patent-eligible under Section 101.

AutoForm Eng’g GmbH v. Eng’g Tech. Assoc., Inc., 2014 WL 4385855 (E.D. Mich. Sept. 5, 2014)

In AutoForm, the district court denied the defendant’s motion for summary judgment of invalidity under Section 101. The court found that the defendant had not provided clear and convincing evidence that the asserted claims were ineligible for patenting. The claims at issue, directed to methods of designing tools for forming sheet metal, were found to “cover more than a mere abstract idea.” A representative claim is as follows:

1. A method for designing a tool for deep drawing of sheet metal to form a sheet metal component having a predefined component geometry, said tool comprising a die, a binder and a punch, whereby the binder is used to fix the sheet metal in an edge zone of the die, before the sheet metal is pressed in a drawing direction by the means of the punch into the die, said tool comprising at least one addendum zone surrounding the component, said addendum zone is generated by a method comprising the following steps:

a. arranging along the component edge at a distance from one another several sectional profiles directing away from the component edge;

b. whereby the sectional profiles are parameterized by the means of profile parameters, the profile parameters being scalar values;

c. laterally interconnecting the sectional profiles by a continuous surface to form the geometry of the addendum zone of the tool, whereby said addendum zone complements the component geometry in the edge zone and runs into the component and the binder with a continuous tangent.

In support of the conclusion that the claims at issue covered more than a mere abstract idea, the court referred to several limitations that were said to narrow the scope of the patent beyond basic concepts of sheet metal tool design. Examples included “arranging sectional profiles along the smooth component edge” and “laterally interconnecting the sectional profiles by a continuous surface to form the geometry of the addendum zone of the tool.”

Data Distribution Techs., LLC v. BRER Affiliates, Inc., 2014 WL 4162765 (D.N.J. Aug. 19, 2014)

In Data Distribution, the district court denied the defendant’s 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss on the ground of invalidity under Section 101. The court found that the procedural posture of the case (before any claim construction) was too early to decide the 101 issue. In particular, the court stated that it could not find based on clear and convincing evidence that there is no plausible construction of the claims that would satisfy the Alice abstractness test. The claims related to a method of maintaining and distributing database information. A representative claim is as follows:

22. A method of maintaining and distributing database information, the method comprising:

communicating with at least one subscriber system to receive user input from a user at said at least one subscriber system;

maintaining a database of information records;

maintaining user records in said database and linking said user records with said information records;

controlling said database such that each information record is associated with at least one user,

wherein controlling said database includes

obtaining for inclusion in a message a plurality of information records having at least one common field entry;

amending said information records in response to user input from said at least one subscriber system; and

serving said message including said plurality of information records having at least one common field entry from said database to said at least one user associated with said information record.

While the court declined to invalidate the claims prior to claim construction, it did find that the claims were directed to an abstract idea under the first prong of the Alice test, and that several of the plaintiff’s arguments under the second “inventive concept” prong of the Alice test were without merit. Specifically, the court said that the plaintiff could not satisfy the Alice test by citing the patent’s figures, limiting application of the claims to the real estate field, emphasizing the speed and efficiency of the claimed system, or stressing the number of claims.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court decision in Alice has been criticized as too subjective and difficult to apply. The lower courts’ response suggests otherwise, with findings of invalidity under Section 101 in 19 of 25 cases. It is too early to tell what ultimate impact Alice will have on the law in this area, though, to draw from another of the Court’s notable patent law decisions, that impact is likely to be “not insubstantial.” In the meantime, patent stakeholders should closely monitor developments in the lower courts and consider the trends highlighted above any time Section 101 eligibility is at issue.

1 Caltech was decided before the Ultramercial case discussed above.

This update was prepared by the Intellectual Property Department at Nutter McClennen & Fish LLP. For more information, please contact your Nutter attorney at 617.439.2000.

This update is for information purposes only and should not be construed as legal advice on any specific facts or circumstances. Under the rules of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, this material may be considered as advertising.

Maximizing the protection and value of intellectual property assets is often the cornerstone of a business's success and even survival. In this blog, Nutter's Intellectual Property attorneys provide news updates and practical tips in patent portfolio development, IP litigation, trademarks, copyrights, trade secrets and licensing.