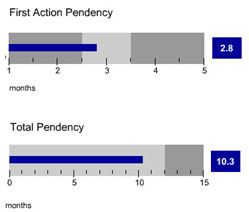

The articles in our earlier editions of the IP Bulletin addressed eight of the most commonly asked questions that arise when completing a U.S. trademark application filing. Once the application has been filed with the USPTO, substantive examination by an examining attorney from the USPTO will commence in due course. In stark contrast to the long waits experienced by patent applicants, the average time between application filing and the issuance of a first Office Action is only 2.8 months at the time of this publication. The average total pendency for a trademark application is only 10.3 months, which indicates that the application is either accepted or rejected by the examining attorney in less than a year.

The articles in our earlier editions of the IP Bulletin addressed eight of the most commonly asked questions that arise when completing a U.S. trademark application filing. Once the application has been filed with the USPTO, substantive examination by an examining attorney from the USPTO will commence in due course. In stark contrast to the long waits experienced by patent applicants, the average time between application filing and the issuance of a first Office Action is only 2.8 months at the time of this publication. The average total pendency for a trademark application is only 10.3 months, which indicates that the application is either accepted or rejected by the examining attorney in less than a year.

The article in our May edition of the IP Bulletin addressed four of the eight most commonly asked questions that arise when completing a U.S. trademark application filing. More particularly, we considered the trademark application form that should be used, the classes of goods or services to include in the application, the items included in the description of goods and services, and appropriate and acceptable specimen of use to be included as part of the application. The other four most commonly asked questions are tackled in this article, including: (5) should I include color or design features as part of my trademark application; (6) what is my filing basis; (7) what is my date of first use; and (8) what other considerations should I be making when preparing my U.S. trademark application?

Our last article in Nutter’s How-to Series on Branding contemplated various territorial considerations that go into deciding where to file a trademark application. Even when a trademark applicant desires protection in multiple countries, or one or more states, most often our readers in this situation will want to first start by filing a United States trademark application. To that end, in our next two articles we address eight of the most commonly asked questions that arise when completing a U.S. trademark application filing.

Once you’ve checked off the five “Cs” and decided on the trademark you want to protect as part of building your brand, you next must decide where you want to file for protection. You see, even though Thomas Friedman has been driving the globalization “Lexus” since before the 21st century, and the reaches of the geography-obliterating, all-encompassing Internet and Mother Web connects Afghanistan to Zimbabwe, trademark rights themselves remain territorial. A single trademark application will not provide global property rights. This fourth article of Nutter’s branding series explores a trademark applicant’s various options regarding where to file a trademark application.

After banging your head against the wall for weeks or even months, your team finally has come up with a name for your new product line. You can see it now—in big lights…on a billboard…in Times Square! Fire up the marketing team, call the printer, order t-shirts, fly banners.

In our first installment, we considered what a trademark is and its relation to a brand. To recap, a trademark is a source-identifier: (in the drugstore) “Ooooh, there’s my CREST toothpaste! I don’t know who makes it, but I do know it will always come from the same place and will always make my mouth feel minty-fresh!”

In early July 2013, the International Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) passed one of the last checkpoints on the path to introducing new generic Top-Level Domains (gTLD) by promulgating a registry agreement that will be entered into by successful gTLD applicants prior to delegation of the new domain space. This means that ICANN could delegate the first of the approved gTLDs (of which there are over 1000!) very soon, consistent with its earlier estimation that the first of the new domains would be operational by the end of July, 2013. Applicants interested in registering their marks in any of the new gTLDs, or those concerned about defending against cyber-squatting or other misappropriation of their marks, should consider submitting their marks to the recently created Trademark Clearinghouse as soon as possible.

If you are a Marxist, you view the world in terms of class struggle; if you are an artist, you see the world as colors and forms; and if you are a trademark lawyer, you see the world in terms of, well, trademarks (and service marks).

The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) recently established that use of a Community trademark within one European Union (“EU”) Member State is not, by itself, sufficient to constitute “genuine use in the Community.” Community trademarks are an economic alternative to national trademarks that provide protection across all twenty-seven EU Member States. One requirement for obtaining protection is that the mark must be put “to genuine use in the Community” within five years of registration.

The Supreme Court unanimously affirmed the dismissal of a challenge to the validity of a trademark in view of the mark owner's unilaterally issued "Covenant Not to Sue." In Already, L.L.C. v. Nike, Inc., Nike accused Already of infringing a trademark on its Air Force 1 sneakers, to which Already responded by alleging Nike's mark was invalid. Nike decided to drop its claims in conjunction with unilaterally issuing a "Covenant Not to Sue," promising not to raise any trademark or unfair competition claims against Already or any affiliated entity based on any of Already's existing footwear designs, or any future Already designs that constituted a "colorable imitation" of Already's current products. Nike relied on its "Covenant Not to Sue" to request that Already’s validity counterclaim also be dismissed because the covenant extinguished any case or controversy; Already desired to maintain its counterclaim of invalidity. The Supreme Court agreed with Nike, affirming the lower court's decision to dismiss Already's counterclaim. The Court ruled that there was no reasonable chance a dispute could ever arise related to the rights at issue between the parties in view of Nike's issued covenant. As a result, the Court concluded that Already lacked standing to challenge the validity of Nike's mark. Practitioners and clients should look to the text of Nike's covenant not to sue for guidance in crafting similar covenants to prevent later attacks against their intellectual property rights.

Maximizing the protection and value of intellectual property assets is often the cornerstone of a business's success and even survival. In this blog, Nutter's Intellectual Property attorneys provide news updates and practical tips in patent portfolio development, IP litigation, trademarks, copyrights, trade secrets and licensing.