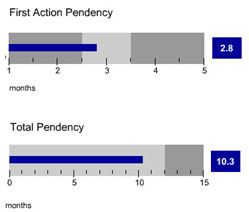

The articles in our earlier editions of the IP Bulletin addressed eight of the most commonly asked questions that arise when completing a U.S. trademark application filing. Once the application has been filed with the USPTO, substantive examination by an examining attorney from the USPTO will commence in due course. In stark contrast to the long waits experienced by patent applicants, the average time between application filing and the issuance of a first Office Action is only 2.8 months at the time of this publication. The average total pendency for a trademark application is only 10.3 months, which indicates that the application is either accepted or rejected by the examining attorney in less than a year.

The articles in our earlier editions of the IP Bulletin addressed eight of the most commonly asked questions that arise when completing a U.S. trademark application filing. Once the application has been filed with the USPTO, substantive examination by an examining attorney from the USPTO will commence in due course. In stark contrast to the long waits experienced by patent applicants, the average time between application filing and the issuance of a first Office Action is only 2.8 months at the time of this publication. The average total pendency for a trademark application is only 10.3 months, which indicates that the application is either accepted or rejected by the examining attorney in less than a year.

There are many reasons why an examining attorney may initially reject a trademark application. When responding to these rejections, an applicant focused on building a brand should be strategic in responding to the rejections to ensure that the brand is protected and even enhanced by the way it responds. Below we discuss some of the more prevalent rejections applicants face during prosecution, including: (1) likely to cause confusion with another mark(s); (2) the mark being merely descriptive (or generic); and (3) the identification of goods and services associated with the mark being unacceptable.

(1) Likely to Cause Confusion with Another Mark(s)

An examining attorney can refuse a trademark application under 15 U.S.C. § 1052(d) when the attorney believes the trademark being applied for resembles a registered mark, or a mark or trade name previously used in the United States by another and not abandoned, such that consumer confusion as to the source or sponsorship of the goods would result.

When an examining attorney refuses an application based on likelihood of confusion, the applicant has a number of options to respond. The applicant should first consider how similar the marks are and whether the examining attorney’s position is tenable. Often the marks are dissimilar enough that the applicant can argue in favor of co-existence between the two marks. The dissimilarity considered by the applicant is not just related to the actual look, feel, and sound of the marks, although those are factors to consider, but rather all thirteen factors established by In re E.I. DuPont De Nemours & Co. are relevant to a determination of likelihood of confusion between two marks. Some of the more effective factors to rely upon when differentiating marks include:

- the dissimilarity of the marks in their entireties as to appearance, sound, connotation, and commercial impression;

- the dissimilarity and nature of the goods;

- the dissimilarity of established, likely-to-continue trade channels;

- the conditions under which, and buyers to whom, sales are made, i.e., “impulse” vs. careful, sophisticated purchasing; and

- the length of time during, and the conditions under, which there has been concurrent use without evidence of actual confusion.

The first of the five factors identified above is self-explanatory. Any differences between the way the marks look, sound, or are used should be brought to the attention of the examining attorney. The second factor identified above is important to remember because even marks that look and sound the same or similar can coexist in the same international trademark class. For example, the trademark ASPIRE for “light-based medical devices” (U.S. Reg. No. 3,702,542) and the trademark ASPIRE for “hearing aids” (U.S. Reg. No. 3,592,759) co-exist in international trademark class 10 (surgical, medical, dental and veterinary apparatus and instruments, artificial limbs, eyes and teeth; orthopedic articles; suture materials) even though they are both medical devices. This is at least because the goods associated with the marks are so different.

The third and fourth factors identified above relate more to purchasing conditions. If the goods in question are sold through different avenues, e.g., to consumers vs. to doctors and hospitals, or even to different departments within the same hospital, that fact tends to be a further reason why confusion is unlikely. Moreover, the more care a consumer is likely to take before making a purchase, the less likely the consumer is to be confused between two allegedly similar marks. The care can be the result of the goods in question being expensive and/or being of the nature a user would investigate before using, for instance a medical device the user would be using on his or herself at home. For example, physicians and pharmacists are considered to be a highly intelligent and discriminating public, and thus the threshold to show a likelihood of confusion amongst this population is significantly high.

The fifth factor identified above is also self-explanatory. The longer two marks have co-existed without issue, the lower the likelihood of consumer confusion.

While it can be effective to argue against the likelihood of confusion by relying on these five factors, or others, an applicant should also carefully consider the implications of having another mark in existence that may, arguably, be similar in some respects. Provided the applicant is confident that not only can the marks coexist, but the applicant’s mark can thrive and become recognizable to its target consumers, the applicant should proceed in arguing against the rejection. However, if there are concerns that use of the other mark may dilute the applicant’s mark, and with it, the applicant’s brand, then the applicant may want to consider an alternative mark.

If an applicant does want to consider an alternative mark, the applicant must do so by filing a new trademark application. While trademark applications can be amended to change the description and associated goods and services, as well as the classes in which it is filed in some instances, an actual change of the mark itself is typically impermissible. Only if the amendment to the mark itself is supported by the originally filed specimens of use, and the proposed amendment does not materially alter the mark, will the amendment be accepted. In some instances, however, amending the application to change the description of goods and services, or the international trademark class, can be effective to overcome a likelihood of confusion rejection.

Another way to address a likelihood of confusion rejection is to obtain a consent agreement from the owner of the trademark being relied upon by the examining attorney. If applicants choose this route, they should be careful to make sure such an agreement does not unnecessarily restrict the applicant’s ability to use the mark in other fields in which it may desire to build the brand.

(2) The Mark Being Merely Descriptive (or Generic)

An examining attorney can also refuse a trademark application under 15 U.S.C. § 1502(e)(1) when the attorney believes the trademark being applied for is merely descriptive (or generic) of the goods and services to which the mark relates. An example of a descriptive mark is the mark “Bed and Breakfast Registry” used for lodging reservation services. The applicant has a number of ways in which it can respond to this type of rejection.

The applicant may chose to respond by amending the application to assert acquired distinctiveness or secondary meaning under 15 U.S.C. § 1502(f). This requires a showing by the applicant that, even though the mark in question may arguably be descriptive, its use in connection with the goods and services has risen to such a level of recognition that consumers expect goods and services sold in association with the mark to be from the trademark owner. Various forms of evidence to support this position are permitted, including previously registered trademarks or proof that the mark in question has been used substantially exclusively and continuously by the applicant in commerce for at least five years.

Another option is to disclaim components of the mark that too closely relate to the goods or services with which the mark is used. A disclaimer is a statement by the applicant on the record that it makes no claim to the exclusive right to use the term in question apart from its use in the mark. For example, a bakery that sells cupcakes and calls itself “Cupcakes on the Square” will typically be required to disclaim the term “cupcake.” This ensures that other bakeries are not precluded from using the word “cupcake.” To the extent a trademark owner has to disclaim a portion of the trademark, the owner should determine if such disclaimer will negatively impact its use of the term in the overall branding strategy.

A third option available to the applicant is to amend the application to be placed onto the supplemental register (as opposed to the primary register) under 15 U.S.C. § 1094. When the mark is amended to the supplemental register, it gives the descriptive mark time to acquire distinctiveness. A registration on the supplemental register allows the applicant to use the ® symbol on the mark in commerce, and it blocks later-filed applications for confusingly similar marks for related goods or services. If the applicant does not have sufficient evidence to establish the mark’s distinctiveness, amending the mark to the supplemental register can protect the applicant’s rights in the mark until distinctiveness (i.e., five or more years of substantially exclusive and continuous use of the mark by the applicant in commerce) is established. If distinctiveness or secondary meaning is subsequently established, the applicant can file an application with the principal register to gain all of the protections of the principal register (e.g., a trademark on the supplemental register does not convey the presumptions of validity, ownership, and exclusive rights to use the trademark that attach with a registration on the principal register).

When considering whether to assert acquired distinctiveness or secondary meaning, either at the time of application or following five or more years on the supplemental register, brand owners should give consideration to the true value of its mark as a brand identifier. As discussed in greater detail in our article about the different levels of trademark protection, a descriptive mark may provide value up-front in helping consumers identify the types of goods and services that are associated with the mark, but it can be harder to use in a long-term branding strategy because the mark may face similarly-situated competitors and it may be more difficult for the term to be used across other, not-as-descriptive platforms. While applicants should not necessarily abandon their branding strategy in view of a “mere descriptiveness” rejection, applicants receiving a rejection for “mere descriptiveness” should at the very least reassess their branding strategy before investing too heavily in it.

(3) The Identification of Goods and Services Associated with the Mark Being Unacceptable

An examining attorney can refuse a trademark application based on the identification of goods and/or services being insufficient, based on 15 U.S.C. § 1112 and TMEP 1402.01. When presenting such a rejection, the examining attorney typically suggests amendments to the identification of goods and/or services that would be acceptable to overcome the refusal.

The suggested changes to the identification of goods and/or services typically include eliminating language the examining attorney considers to be vague. It may also include eliminating one or more identified goods or services. Because goods or services that are removed from the identification cannot later be added, applicants should only remove the goods or services that they never plan to use.

Further, if the examining attorney rejects a mark because the goods and/or services listed in the application are too broad, the applicant can amend to narrow the goods or services listed. For example, if the examining attorney has rejected the mark in “food services,” the applicant can amend the mark into “cafeteria staffing,” to limit the services. An amendment of this nature can also be used to overcome likelihood of confusion rejections where appropriate. Applicants should be mindful that the identifications cannot be broadened during prosecution. Only amendments that narrow the identification of goods and services are acceptable.

Sometimes marks will be rejected for filing in more than one class of goods and/or services. If this is the case, the applicant has three options. First, the applicant can amend the goods and/or services to include only one class, keeping in mind that goods and/or services cannot be rejoined later. Second, the applicant can pay a fee for filing a mark in more than one class. If the applicant wishes to do so, this will be called a “multi-class application,” and the applicant will have to pay a filing fee for each class. Another option is to divide the application into two or more separate applications. If the application is divided, the applicant will have to pay a filing fee for each application. A benefit to dividing the application is that, if an Office Action pertaining to only one class is outstanding, a response is not due in the newly filed divisional application in the class in which the Office Action is not pending, i.e., the newly filed divisional application may be in condition for registration, regardless of the rejections against the originally filed application. In both of the latter options the applicant will need to consider its use, or potential use, of the mark in the various classes versus the cost of filing a multi-class or divisional application. It is not likely that having separate applications will impact the branding strategy.

Conclusion

When responding to an Office Action, applicants looking to build their brand should consider the impact any arguments and amendments may have on their branding strategy. The goal should not be just to get a registered trademark, but instead to build a trademark portfolio that is tailored to the products and services that the applicant sells. As arguments are made of record, the applicant should give careful consideration to the future of the brand and other goods and services with which the applicant may eventually want to use the trademark.

In our next article, we will turn our focus to what trademark owners should do with their trademark registration after it has been received.

This update was prepared by Nutter's Intellectual Property practice. For more information, please contact your Nutter attorney at 617.439.2000.

This update is for information purposes only and should not be construed as legal advice on any specific facts or circumstances. Under the rules of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, this material may be considered as advertising.

Maximizing the protection and value of intellectual property assets is often the cornerstone of a business's success and even survival. In this blog, Nutter's Intellectual Property attorneys provide news updates and practical tips in patent portfolio development, IP litigation, trademarks, copyrights, trade secrets and licensing.