The examiner count system is the stick by which a patent examiner’s production is measured. Although the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office(USPTO) does set expected time limits for each task, examiners’ production goals are met by receiving “counts,” which are accrued by completion of various tasks associated with the examination process. Under the current count system, more counts are granted for tasks performed early in prosecution to provide an incentive for examiners to “dispose” of cases quickly—either through abandonment or the granting of a Notice of Allowance. Thus, the count system serves as a reminder that patent examiners and patent applicants are not opponents, but rather members of the same team who are intended to work together to move patent applications through the system.

The Leahy-Smith America Invents Act provided for post issuance proceedings that allow the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (the PTAB) of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) to review issued patents for validity. These proceedings have become a popular choice for defendants in patent litigation due to a lower standard for proving that a patent is invalid, the opportunity to participate in the proceedings, and a relatively shorter duration and lower costs when compared to litigation. One type of post issuance proceeding is an Inter Partes Review (IPR), in which a petitioner may challenge the validity of one or more claims of an issued patent under 35 U.S.C. §§ 102 or 103 in view of (only) patents or printed publications. The PTAB must grant the petition if the petitioner demonstrates that there is a “reasonable likelihood” that it can prove at least one claim is invalid. If the petition is granted, the PTAB is given one year to issue a final determination on the claims at issue.

On March 28, 2012, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published its first-ever guidance document on the risk-benefit analysis that forms the cornerstone of medical device approval.1 The 2012 guidance addressed considerations governing pre-market approval (PMA) and de novo submissions, but notably absent from the final version of the 2012 guidance was an explanation of the risk-benefit analysis for premarket notifications [510(k)]. On July 15th of this year, more than two years later, and amid a flurry of FDA guidance documents,2 the FDA released a draft guidance document specifically focused on the risk-benefit analysis for devices undergoing the 510(k) process. Although remarkably similar to the 2012 guidance, the 2014 guidance includes a handful of subtle differences that may be important for device manufacturers to keep in mind when making any type of submission.

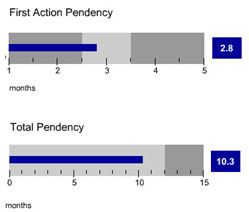

The articles in our earlier editions of the IP Bulletin addressed eight of the most commonly asked questions that arise when completing a U.S. trademark application filing. Once the application has been filed with the USPTO, substantive examination by an examining attorney from the USPTO will commence in due course. In stark contrast to the long waits experienced by patent applicants, the average time between application filing and the issuance of a first Office Action is only 2.8 months at the time of this publication. The average total pendency for a trademark application is only 10.3 months, which indicates that the application is either accepted or rejected by the examining attorney in less than a year.

The articles in our earlier editions of the IP Bulletin addressed eight of the most commonly asked questions that arise when completing a U.S. trademark application filing. Once the application has been filed with the USPTO, substantive examination by an examining attorney from the USPTO will commence in due course. In stark contrast to the long waits experienced by patent applicants, the average time between application filing and the issuance of a first Office Action is only 2.8 months at the time of this publication. The average total pendency for a trademark application is only 10.3 months, which indicates that the application is either accepted or rejected by the examining attorney in less than a year.

Currently, the average time a patent applicant waits to receive a first Office Action from the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) is 18.9 months. The total pendency for a patent application before a final disposition is achieved (e.g., Notice of Allowance issued, Request for Continued Examination filed, or application is abandoned) is 27.5 months. This number jumps to 37.9 months when applications in which RCEs are filed are included. These long delays can be frustrating for patent applicants. Start-up companies looking to secure patent protection to attract investors can find this long delay at the USPTO detrimental to the company’s ability to survive. Further, applicants looking to use information from U.S. patent prosecution to make decisions about which countries to enter following the filing of a Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) patent application may be left making expensive foreign filing decisions without much information about the likelihood of securing a patent.

On November 1, 2014, the European Patent Office (EPO) will implement a revision to Rule 164 EPC that allows Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) applicants to have more than one invention searched when a unity of invention objection is present, regardless of whether the EPO was selected as the International Searching Authority (ISA) during the international phase. Under current practice, if the EPO is not the selected ISA, a supplemental European search report will address only the first invention mentioned in the claims, and any further inventions can only be pursued through divisional practice. Conversely, however, if the EPO is the selected ISA, applicants can request and pay for additional searches before selecting the invention to be pursued.

On August 4, 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released Draft Guidance on determining eligibility of a biological drug for regulatory exclusivity.

Under the Public Health Service Act (PHS Act), as amended in 2010, an abbreviated biosimilar application can be accepted by the FDA, but not until 4 years after the first licensure of the original reference product and, once accepted, such an application cannot be fully approved by the FDA for a period of 12 years from the reference’s first licensure. This reference product exclusivity is granted independently of any patent exclusivity, and therefore, by itself, provides a significant incentive to the sponsor of a Biologic License Application (BLA) who obtains the first licensure status. The date of first licensure is also critical to the timing of a follow-on biosimilar entry to the market.

The Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (AIA) introduced a number of important changes to U.S. patent law. Many of the provisions in the AIA do not apply to patent applications that have an effective filing date prior to March 16, 2013 (pre-AIA applications). For a number of reasons that have been well documented, it can be desirable to preserve an application’s status as a pre-AIA application.

On the same day in early June, the United States Supreme Court issued two opinions addressing patent law issues related to inducement and indefiniteness —Limelight Networks, Inc. v. Akamai Technologies, Inc. and Nautilus, Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc., respectively. In both cases, the nation’s highest court unanimously reversed the Federal Circuit. In doing so, the Court simultaneously raised the bar for patentees with respect to patent infringement and lowered the bar for alleged infringers with respect to invalidity. The decision provides a salient reminder of some important claim drafting strategies for current and future patent applicants.

Active Inducement of Infringement

The Patent Act provides that “[w]hoever actively induces infringement of a patent shall be liable as an infringer.” In Limelight, the accused infringer Limelight Networks, Inc., was alleged to have actively induced infringement of a method patent by carrying out some steps of the claimed method and encouraging its customers to carry out the remaining steps. For purposes of this case, the Supreme Court assumed that infringement of all the method steps could not be attributable to a single party, either because Limelight had not actually performed the steps or because it did not direct or control others who performed them. Accordingly, the Supreme Court reversed the Federal Circuit’s decision and found that Limelight could not be liable for active inducement of infringement. In doing so, it reinstated the principle that liability for induced infringement must be predicated on direct infringement. The Court, however, made specific note that the Federal Circuit on remand will have the opportunity to revisit the question of direct infringement by Limelight under 35 U.S.C. § 271(a). For the time being, however, Limelight has escaped a finding of liability by dividing the performance of method steps between more than one party.

Indefiniteness

In addition to reversing the Federal Circuit’s holding concerning active inducement of infringement, the Court in Nautilus set forth a new test for patent definiteness when considering validity of a patent claim in view of 35 U.S.C. § 112. In particular, the Court held that “a patent is invalid for indefiniteness if its claims, read in light of the specification delineating the patent, and the prosecution history, fail to inform, with reasonable certainty, those skilled in the art about the scope of the invention.” This new standard replaces the Federal Circuit’s long-standing “insolubly ambiguous” test, which directed lower courts to invalidate claims only if they are not “amenable to construction,” meaning that claims should survive so long as a court could “ascribe some meaning” to them. In overturning that standard, the Supreme Court found that it “can leave courts and the patent bar at sea without a reliable compass.”

Because the Court remanded the case back to the Federal Circuit with the instruction to apply the new standard to the claims at issue, the application and breadth of the newly pronounced indefiniteness standard are uncertain. While the Court found that the old standard was too lenient toward ambiguous claims, it cautioned that “[s]ection 112…entails a ‘delicate balance’” that “must take into account the inherent limitations of language,” and allow for “[s]ome modicum of uncertainty,” while also requiring claims to “be precise enough to afford clear notion of what is claimed.” The Court also pointed out the importance of viewing the claims from the point of view of a person skilled in the art, and that such an investigation “may turn on evaluations of expert testimony.” Thus, the new standard appeals to a rule of reason, and its application likely will involve an intense factual investigation. In addition, the Court restricted its holding to the 2006 version of the Patent Act, which was in effect prior to enactment of the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act in 2012. It will thus be left to future cases to determine whether the Supreme Court’s new standard will be applied to patents filed after September 16, 2012.

Claim Drafting

Even with the uncertainty surrounding indefiniteness, patent applicants can employ certain claim drafting strategies to protect their interests in view of Limelight and Nautilus. For example, to circumvent the divided infringement issue in view of Limelight, method claim language can be drafted from the perspective of a single actor that practices all of the steps of the claimed process. While this can in some cases be more difficult and awkward, claims that focus on the behavior of one actor are more likely to hold up in infringement litigation and afford patentees the greatest likelihood of protection.

Further, while the exact meaning of the new “reasonable certainty” standard for claim definiteness is unknown, it seems evident that a greater level of clarity in describing the scope of an invention will be required going forward. For example, certain claim limitations based on inherent characteristics and functional language may not be sufficient to satisfy definiteness under 35 U.S.C. § 112 after Nautilus. To guard against this possibility while retaining the broadest coverage, applicants should ensure that their specification includes broad disclosure along with more specific examples of the embodiments of the invention. Applicants should also be sure to draft claims in the same manner, e.g., by including broader functional language in an independent claim and more specific limitations in dependent claims. Under such a strategy, the invention can remain protected under the new standard by the narrower claims even if the broader claims are deemed indefinite.

While these strategies themselves are not novel, their importance is highlighted by the Supreme Court’s recent decisions.

This update was prepared by Nutter's Intellectual Property practice. For more information, please contact your Nutter attorney at 617.439.2000.

This update is for information purposes only and should not be construed as legal advice on any specific facts or circumstances. Under the rules of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, this material may be considered as advertising.

Despite being dismissed by the Federal Circuit before reaching its highly anticipated substantive issues regarding patent eligibility, the ruling in Consumer Watchdog v. Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation nonetheless significantly alters the patent litigation landscape. Consumer Watchdog (CW), a nonprofit waging a seven-year campaign to invalidate the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF) stem cell patent, saw its battle come to an abrupt end when the Federal Circuit held that it did not have an injury in fact sufficient to confer Article III standing to appeal a United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) decision in federal court. The ruling limits the reach of the statute permitting appeals of USPTO rulings to the constitutional boundaries set by Article III, leaving some third-party challengers stuck with the USPTO as their only available forum.

Maximizing the protection and value of intellectual property assets is often the cornerstone of a business's success and even survival. In this blog, Nutter's Intellectual Property attorneys provide news updates and practical tips in patent portfolio development, IP litigation, trademarks, copyrights, trade secrets and licensing.