Importance of design patent applications is steadily increasing. Design patents have traditionally been considered not a particularly strong intellectual property (IP) protection tool. In its 2008 en banc decision in Egyptian Goddess v. Swisa, the Federal Circuit brought some clarity into determining design patent infringement by holding that that the ordinary observer test, in view of prior art, was the “sole test” for determining infringement. Additionally, the jury award of $290 million to Apple in the familiar Apple v. Samsung battle involving alleged infringement by Samsung of Apple’s iPhone design patents further increased public interest in the role of design patents in IP protection. In view of these decisions, and the relative ease and low cost of obtaining design patents, design patents have been gaining popularity among large and small companies alike.

The increase in appreciation of a design patent’s potential as an IP protection tool encourages an understanding of nuances of developing a commercially valuable design patent portfolio.

Design Patents Overview

Unlike utility patents that protect functionality of a product, design patents protect only the look of the product, or its visual ornamental characteristics. A unique look of a product can thus be protected by a design patent. Some companies choose to protect their invention using both utility and design patents, to have a more complete protection. For example, a utility patent application can be filed to protect some new functionality of a device, while a design application can be used to protect an overall look of the device or some of its parts.

Prosecution of a design patent application is typically relatively uneventful. There is only one claim, and no other description of the invention is required. And even the sole claim only points to the ornamental design as shown in the drawings. The cost of obtaining a design patent is significantly lower than that of a utility patent, and no maintenance fees are required. The examination of a design patent application involves checking for compliance with formalities and ensuring that the drawings are complete. Rejections altogether are infrequent, and rejections based on prior art are particularly rare.

However, as the recent case Pacific Coast Marine Windshields Ltd. v. Malibu Boats demonstrates, the seemingly easy process of obtaining a design patent can be a trap for the unwary. In this case, the Federal Circuit held that prosecution history estoppel, a well-established doctrine applied to utility patents, can apply in design application cases as well.

Pacific Coast Marine Windshields Case Background

The design patent at issue in Pacific Coast Marine Windshields was U.S. Patent No. D555,070 (the ‘070 patent) on a design of a boat windshield, assigned to Pacific Coast. An application that resulted in the ‘070 patent was filed in 2006 with 12 drawings and with a claim that recited “ornamental design of a marine windshield with a frame, a tapered corner post with vent holes and without said vent holes, and with a hatch and without said hatch, as shown and described.”

During prosecution, the Examiner issued a restriction requirement indicating that the application included five “patentably distinct groups of designs.” The first group, which the applicant elected to proceed with, was referred to by the Examiner as a “marine windshield with hatch and four circular venting holes.” In the response to the restriction requirement, the patentee canceled Figures 7-12 and amended the claim to delete any reference to the vent holes. In particular, the claim was amended to recite “ornamental design of a marine windshield with a frame and a pair of tapered corner posts, as shown and described.” In the response to the restriction requirement, the applicant noted that it “has amended the claim to more precisely represent the invention.” No arguments with respect to the restriction requirement were provided. The application eventually issued with the claim reciting “the ornamental design for a marine windshield, as shown and described.” Pacific Coast later obtained a divisional design patent of the original application, on a windshield with no holes in the corner. No other divisional applications have been filed.

In 2011, Pacific Coast sued Malibu Boats, LLC, Marine Hardware, Inc., Tressmark, Inc., MH Windows, LLC, and John F. Pugh (collectively “Malibu Boats”) in the Middle District of Florida alleging infringement of the ‘070 patent. The district court granted Malibu Boats’ motion for partial summary judgment of non-infringement on the grounds of prosecution history estoppel, stating that “during prosecution, the applicant had surrendered the designs reflected in the canceled figures and amended the claim ‘in order to obtain the patent.'”

Federal Circuit Decision

The Federal Circuit reversed, holding that although “there was a surrender of claim scope during prosecution” due to prosecution history estoppel, the accused design was not “within the scope of the surrender,” and remanded for further proceedings.

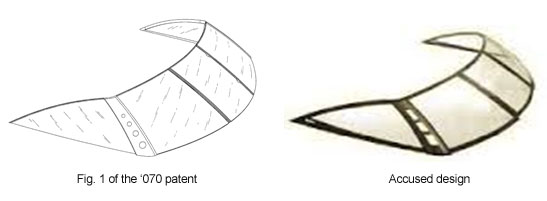

A comparison of the representative Figure 1 of the ‘070 patent and the accused design are shown below:

As shown, Figure 1 of the ‘070 patent is a boat windshield with four round holes on the corner post. The accused design is a boat windshield having three trapezoidal vent holes on the corner post.

In this case, the Federal Circuit had to decide as an issue of “first impression” whether prosecution history estoppel applies to design patents, even though the claimed scope is defined by drawings rather than language. The Federal Circuit considered: (1) whether there was a surrender, (2) whether it was for reasons of patentability, and (3) whether the accused design is within the scope of the surrender.

With respect to the first prong of the analysis, the Court stated that “[b]y cancelling figures showing corner posts with two holes and no holes, the applicant surrendered such designs and conceded that the claim was limited to what the remaining figure showed— a windshield with four holes in the corner post – and colorable imitations thereof.” Also, referring to the amendment to claim 1 made by the applicant, the Court concluded that, by “removing the broad language referring to alternate configurations and cancelling the individual figures showing the unelected embodiments, the applicant narrowed the scope of his original application, and surrendered subject matter.”

Pacific Coast argued that only surrenders to avoid prior art are within the doctrine of prosecution history estoppel. However, the Federal Circuit disagreed, stating that in design patents, “the surrender resulting from a restriction requirement invokes prosecution history estoppel if the surrender was necessary … ‘to secure a patent.'” Thus, as regards the second prong, the Court concluded that the claim scope was indeed limited for reasons of patentability – in order to secure a patent. In addition, the Court noted that a restriction requirement issued in a design application is not as “a mere matter of administrative inconvenience,” but a way to ensure that a design patent claims only one design.

Considering the third question, the Federal Circuit disagreed with the district’s court holding that Malibu Boats’ accused design was within the scope of the surrendered subject matter. The Court concluded that the applicant surrendered only the two-hole design but not the accused three-hole design. Thus, the Court held that prosecution history estoppel did not bar Pacific Coast’s infringement claim, reversed the district court’s grant of summary judgment of noninfringement, and remanded for further proceedings.

Lessons from Pacific Coast Marine Windshield

The decision in Pacific Coast Marine Windshield demonstrates the importance of carefully thinking through a deceptively simple process of prosecuting a design patent application. Thus, when the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office determines that an original design patent application includes more than one patentably distinct design and issues a restriction requirement, an applicant should not only elect to continue prosecution of one of the designs, but should also consider filing divisional applications directed to non-elected designs. Such an approach can ensure complete coverage of all inventive designs. Following this simple rule, a patentee can build a strong design patent portfolio that can be used against potential infringers in the future.

Another takeaway is a reminder that in preparing and prosecuting a patent application on a design of a product, it is important to consider all possible variations of the design and not limit the application to a specific one, especially given the relatively low cost of obtaining design patents. If a company prefers to avoid dealing with restriction requirements, it can consider filing separate applications on specific designs.

Lastly, the applicant of a design patent should be aware that amending the claim of a design patent application can potentially limit the scope of that application, which may cause undesirable complications when the patent is enforced.

This update was prepared by Nutter’s Intellectual Property practice. For more information, please contact your Nutter attorney at 617.439.2000.

This update is for information purposes only and should not be construed as legal advice on any specific facts or circumstances. Under the rules of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, this material may be considered as advertising.

Maximizing the protection and value of intellectual property assets is often the cornerstone of a business's success and even survival. In this blog, Nutter's Intellectual Property attorneys provide news updates and practical tips in patent portfolio development, IP litigation, trademarks, copyrights, trade secrets and licensing.