Trending publication

The Real Impact (Winter 2024)

Print PDFRead the Winter 2024 edition of The Real Impact.

The Spectrum of 501(c)(3)s: There's Not Just One Kind

By Erin Whitney Cicchetti

Year-end is a popular time to have charitable giving goals on the mind. There are a variety of different ways to implement these goals, including contributing to an already existing charity, establishing a donor advised fund, or setting up a new, independent section 501I(3) charitable organization. Each of these charitable giving tools has its own pros and cons, and while some individuals focus solely on one of these methods, others use a multipronged approach to optimize their philanthropic impact.

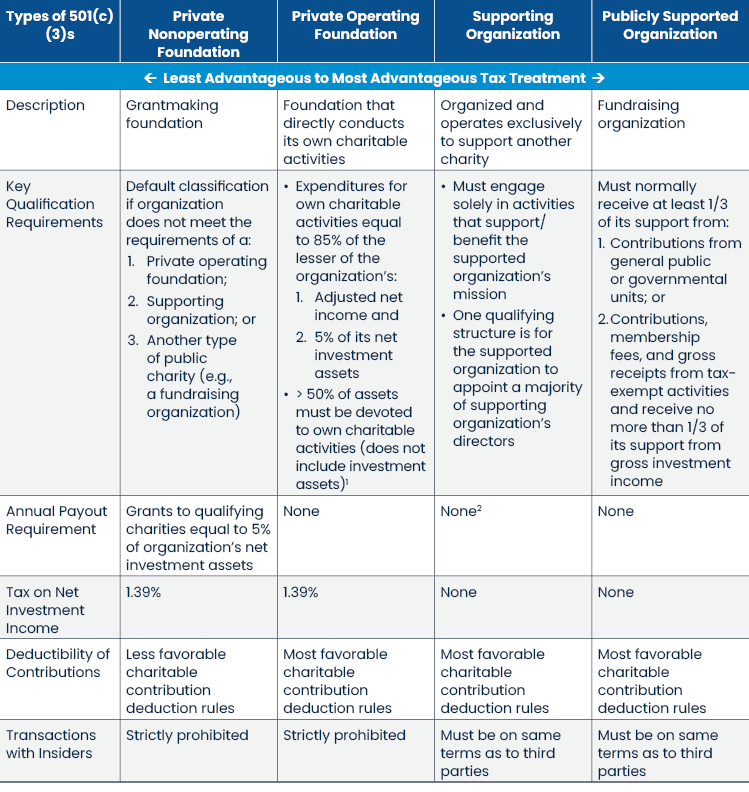

This article focuses on the establishment of a new charity. There are many different decision points to consider in doing so. What will be the organization’s charitable mission? Will the organization fundraise and, if so, how? Who should be on the organization’s governing body? And, of course, what will the organization be named? One of the most important—and complex—considerations, however, is the organization’s specific federal tax status. Being described under section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code is how charitable organizations are designated as tax-exempt, but not all section 501(c)(3) organizations are treated equally. There are many different types of 501(c)(3) organizations. Under the Code, a 501(c)(3) charitable organization is, by default, treated as a so-called “private nonoperating foundation” (i.e., a grantmaking foundation), unless it can prove to the Internal Revenue Service that it satisfies the requirements of a more favorable classification, such as a supporting organization or some type of public charity. Because there are qualification requirements for the more advantageous tax classifications, not all charities will be eligible, but there is advanced planning that can be done to ensure nothing is being left on the table.

Below is a summary chart of the most common types of section 501(c)(3) organizations, including a brief description, key qualification requirements, annual payout requirements (if any), and other important attributes to consider. It is organized from least advantageous from a tax perspective on the left, to most advantageous on the right.

Mass Leads Act: Relief Granted in Massachusetts for Nonprofits and their Directors

By Melissa Sampson McMorrow

Recently, the Massachusetts state legislature passed and Governor Healey signed into law the “Mass Leads Act” (officially H5100), which Healey described as “essential to keeping the Massachusetts economy strong and adaptable in a rapidly changing world.” Wedged within provisions designed to infuse nearly $4 billion across different sectors in the Commonwealth’s economy – notably offering hundreds of millions of dollars of long-term state support to the life sciences and climate industries – the bill includes two provisions of note relevant for nonprofits operating in Massachusetts.

First, the Mass Leads Act extends the statutory protections for volunteer nonprofit directors also to those directors who receive limited stipends. Previously, someone serving as a director on the board of a nonprofit could not receive any compensation for their time and efforts without forfeiting personal civil liability protections under Massachusetts law (M.G.L. ch. 231, sec. 85W). The Mass Leads Act amended this law to allow for a stipend of up to $500, which puts Massachusetts state law on par with the Federal Volunteer Protection Act.

The Mass Leads Act also raises the threshold for financial reporting requirements for nonprofits. Nonprofits now only need to submit financial statements that have been reviewed or audited by an independent certified public accountant if they have gross support and revenue of more than $500,000 in a fiscal year and whether the statements must be audited or reviewed depends on whether the gross support and revenue exceeds $1 million. These thresholds used to be $200,000 and $500,000, respectively. These increases mean that fewer nonprofit organizations will require an audit and smaller nonprofits with revenues under $500,000 will not have to undergo costly reviews and audits to be in compliance.

These changes are effective immediately and promise to have a small, but meaningful, impact on nonprofit operations. For more information, see the explanation on the Massachusetts Attorney General’s website.

Private Foundation Grantmaking: 10 Best Practices

By Erin Whitney Cicchetti

December is a popular time for philanthropists and donors to create or add significant assets to grantmaking foundations. As a firm that regularly represents both grantmakers and charities seeking grants, we often notice systematic inefficiencies in the grantmaking process that could be improved to facilitate a more efficient deployment of philanthropic funds that, in turn, could enable both foundations and charities to accomplish their charitable missions more effectively. Often, we find that foundations have significant assets in need of a worthwhile project and charities have excellent plans to advance their missions but struggle to identify like-minded funders. Foundations can do their part by adopting well defined, effective grantmaking practices, as we describe below.

- Develop a vision for the foundation to guide its long-term direction. A vision statement helps foundation trustees, potential grantees, and the public understand the fundamental objectives and long-term goals of the organization.

- Develop a mission statement for the foundation to drive its immediate decisions. Mission statements reduce a foundation’s vision into more concrete, specific, and temporal terms. Neither a vision statement nor mission statement prevent a foundation from making a grant to any member of the charitable class described in its formation documents.

- Determine, and articulate to potential grantees, the types of grants the foundation will make. A foundation may consider funding a particular project, providing general operating support, contributing to a capital campaign, helping to build an endowment, funding scholarships, supporting pilot projects, sponsoring research or public policy work, or assisting in the expansion of existing programs.

- Establish processes for reviewing requests and selecting grantees. A foundation may accept grant proposals or may, instead, decide to independently select grantees. If a foundation decides to accept proposals, having processes in place to review grant proposals creates consistency and efficiency.

- Engage in pre-grant diligence. Before deciding to give a grant, investigate the prospective grantee’s ability to support the foundation’s goals. Using outside reviewers, site visits, and other sources of information may be an appropriate part of pre-grant due diligence.

- Consider how the timing of grant payments may further the foundation’s goals. Making future grant payments conditional on the achievement of certain benchmarks or on obtaining matching grant commitments may be appropriate.

- Communicate the foundation’s expectations in a grant agreement. Beyond notifying the grantee of the amount of the grant, a grant notification/agreement allows the foundation to explain what it will expect of the grantee.

- Maintain contact with grantees to ensure progress on the foundation’s mission. While the Internal Revenue Service only requires a foundation to monitor grants to non-charities (called “expenditure responsibility”), foundations generally benefit from receiving information back from all grantees during the period of the grant.

- Formally “close” each grant. After all payments have been made under a grant and the term of the grant is coming or has come to an end, a grantee should be asked to provide the foundation with a final report. Once a final report is submitted and reviewed, a closed grant file should be created to preserve key records for future reference.

- Use the systems that work for the foundation. A foundation’s size, the number of people involved, and its long-term goals should all inform the extent of its grantmaking processes.

This update is for information purposes only and should not be construed as legal advice on any specific facts or circumstances. Under the rules of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, this material may be considered as advertising.

[1] There are other ways to qualify as a private operating foundation, but this test is the most common.

[2] “Type III” supporting organizations must make grants to their supported organization equal to the greater of (1) 85% of their adjusted net income and (2) 3.5% of their investment assets.